TRINIDAD AND Tobago cyclist Nicholas Paul said his Olympic debut at 2020 Tokyo Games was a learning experience and he is already looking ahead to the 2024 Paris Olympics.

National long jumper, coach recover from covid19

Trinidad and Tobago men’s long jumper Andwuelle Wright and his coach Wendell Williams were able to get a small taste of the 2020 Tokyo Olympic experience as they participated in the closing ceremony, on Sunday morning (TT time).

Sibling of Olympic cyclist Browne: 'People don't see the sacrifices'

Trinidad and Tobago cyclist Kwesi Browne's ninth place finish in the keirin at the Olympics on Saturday is being hailed by his family who have seen the sacrifices he has made to reach Tokyo.

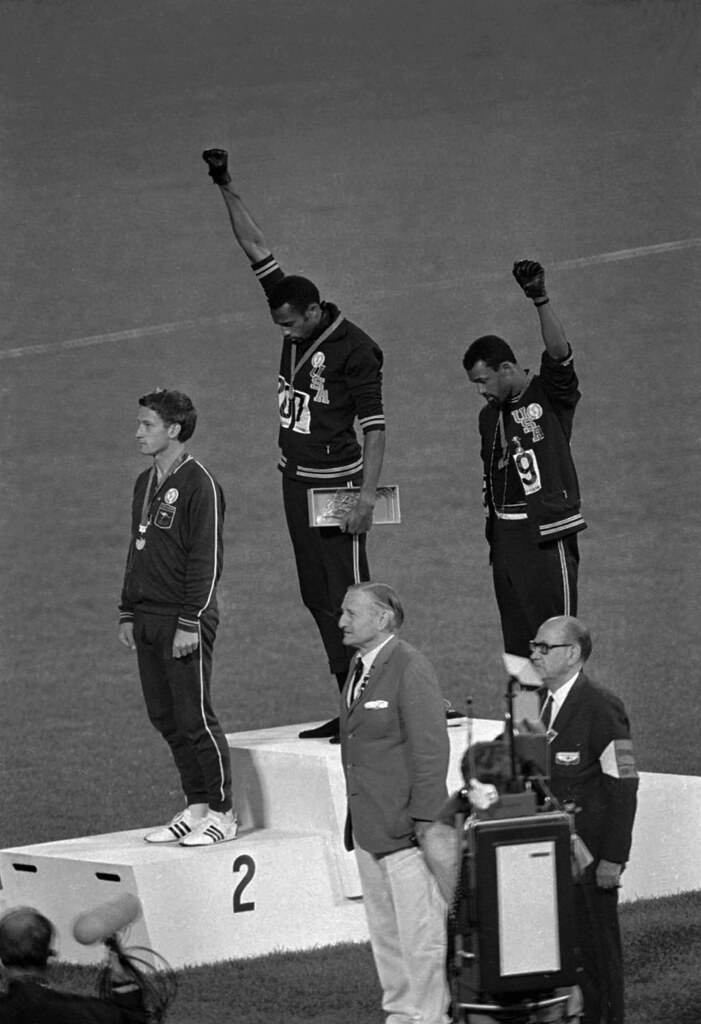

The Olympic movement is just as racist as ever

As the Olympics reached its usual anti-climactic conclusion it felt like an event that took place in 2020 rather than 2021. Apparently, no one gave the International Olympic Committee (IOC) the memo that last year’s summer of protest has forever banished the ridiculous idea that sport is separate from politics and protest. From football, to basketball, to car racing and every sport in between we have seen a year of protests from athletes using their platforms to highlight the issue of racial injustice. But whilst they relaxed rule 50 that prohibits any ‘demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda’ to allow teams to take the knee before games, the IOC banned displaying any of the images on their official social media pages. At least we can treasure having a perfect example of liberal racist doublespeak to use as a teachable moment.

From Tokyo to Tokyo, it has been 57 years of change for the Olympic Games

The Olympic Flame dies here in Tokyo after an Olympic Games that have, for all sorts of reasons, been like no other.

The Olympic movement itself has seen many changes since the last time Tokyo hosted the Olympics in 1964. It has dealt with political boycotts, come to terms with the entry of professionalism, developed a greater awareness of gender equality and also confronted the problems of doping.

Drugs, of course, have haunted the Games for much of the intervening years, the problem so severe that it was necessary to create a world anti-doping agency, but from this distance, the 1964 Games sometimes seem like a beacon of innocence -- they were the first to be beamed by satellite and heralded the transformation of the Games into a truly global phenomenon.

In 1964, the changing political world was reflected in microcosm at the ceremonies. At the opening, marathoner Trevor Haynes was the proud flagbearer for Northern Rhodesia. When the Flame was extinguished a fortnight later, his nation had independence and a new identity.

It was a time when many new nations were achieving independence. The green, gold, black and red flag of Zambia was seen on an international stage for the first time.

There was the growth of African sport, especially in distance running. Ethiopia’s marathon champion Abebe Bikila was the only athlete from Africa to win gold. Mohammed Gammoudi took silver for Tunisia in the 10,000 metres. Four years later, every gold from 1500m and above was won by an athlete from an African nation.

Kipchoge Keino, emblematic of Kenya's success, had carried the Kenyan flag in Tokyo. He went on to win 1500m gold and 5000m silver in Mexico, before winning steeplechase gold in Munich. His countryman Eliud Kipchoge won the men's marathon in Sapporo at Tokyo 2020 as the latest in a distinguished Kenyan roll of honour.

In the 1960s, the newly independent African nations lobbied for the exclusion of South Africa as a protest against the apartheid system that discriminated on the grounds of skin colour. Although the International Olympic Committee (IOC) did not formally expel South Africa from the Olympic movement until its Amsterdam session in 1970, the Republic’s Olympic isolation effectively began at Tokyo. They did not return to the Olympic fold until 1992.

Then in 1980 came the most serious threat to the future of the Games yet seen. American President Jimmy Carter called for a boycott of the Moscow Olympics to protest against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. It was a move that caused bitterness as Canada, Japan and Germany supported Carter’s position and stayed away. Amongst many athletes to miss out were Japanese judoka Yasuhiro Yamashita, now Japanese Olympic Committee President and IOC President Thomas Bach.

The future of the Olympic movement looked bleak.

Los Angeles had been the only candidate for the 1984 Olympics. With the exception of Romania, the Soviet bloc boycotted the Games in what many saw as retaliation for the American-led boycott of 1980.

In 1988, only two cities bid to host the Olympics. The South Korean capital Seoul won convincingly against the Japanese city of Nagoya, but many predicted disaster as Seoul was still an authoritarian military regime.

And yet, despite the looming doom, an unprecedented 140 nations competed in Los Angeles and the profits were estimated to be around $232 million (£167million/€197million). In the years that followed LA's success, there was no shortage of candidate cities, although more recently that trend has receded -- Paris and Los Angeles were originally rivals for the 2024 Games before the IOC decided on a double award.

Another significant change in the Olympic landscape was the country that hosted the 1964 and 2020 Games. Japan’s Olympians have won over 50 medals here but it was at the 1964 Games that they first emerged onto the world stage.

Their women’s volleyball team, originally drawn from workers at an Osaka factory, were known at the time as the "Oriental Witches". They were heavily favoured for gold and performed superbly to become the first Olympic champions in the sport.

The Japanese also had their wish as judo made its Olympic entry, though gold in the open category went to the Dutchman Anton Geesink. Judo, while missing the 1968 Games, has since become a regular Olympic sport.

Since then, the sports programme has been transformed. By Tokyo 2020, karate, surfing, skateboarding and sport climbing had all taken their place and more traditional sports such as fencing, shooting and archery have adapted their formats to remain on the programme.

There has also been evolution in gender equality. At the 1964 Games, women took part in athletics, swimming, diving, equestrianism, fencing and gymnastics, but women’s events in rowing and cycling were not included until 1976 and hockey had to wait until 1980.

At the athletics competitions in 1964, the longest distance open to women was the 800m, won by British runner Ann Packer. Not until 1984 was the marathon introduced for women and even then, there were some who were hesitant. Then again, all the IOC members at that time were men. Monique Berlioux, who became a senior official in Lausanne in the late sixties wrote those "who consider that the sports field is no place for a woman" are "still too numerous".

When women were belatedly allowed to compete at longer distances, runners from Africa and Asian countries began to dominate. By 2000, Sydney organisers were keen to recognise the contribution of women to the Olympics. All the Torchbearers in the stadium were women and Cathy Freeman lit the cauldron.

The Olympic charter now explicitly forbids discrimination on the grounds of sexuality, but in the sixties, the idea of gender verification was by no means as sophisticated. To start with, the test was a physical examination, though later swab tests were introduced.

Poland’s 4x100 relay gold medallist Ewa Kłobukowska failed a gender test in 1967. It showed unusual genetic patterns and she was stripped of her world records although allowed to retain her medals. Later research showed the tests had been inaccurate.

Although explicit gender tests were discontinued in the late nineties, sports authorities have more recently wrestled with the conundrum of female athletes with hyperandrogenism, meaning they have elevated levels of testosterone in their bodies. The case of South African runner Caster Semenya thrust the question of gender identity into the international Olympic spotlight, and transgender weightlifter Laurel Hubbard has raised trans issues in Olympic sport, too.

Another major shift is the professionalisation of sport. The majority of champions at Tokyo 2020 are full-time athletes. Back in 1964, the rules of the Olympics insisted that competitors be strictly amateur.

There was no more ardent advocate than IOC President Avery Brundage. He saw himself as the high priest of amateurism and never missed an opportunity to promote the evils of those who were paid for playing sport. Even then, many saw him as an anachronism in a changing world.

Many Eastern bloc nations were already defacto professionals in everything but name. It was a similar story with collegiate athletes in the United States. Brundage waged a bitter war on professionalism, with the Winter Olympics the target of much of his anger -- he might well have cheerfully abolished them and made a point of not attending the alpine skiing events at the 1968 Games in Grenoble.

Then in 1972, the case of Karl Schranz, the supreme Austrian skier at that time proved a flashpoint.

"Brundage had a little black book," Schranz told insidethegames in 2014. He stood accused of using his likeness for commercial purposes. This was strictly against the rules and Brundage insisted that Schranz be thrown out of the 1972 Sapporo Games. When Schranz attempted to put his case to the IOC, he claimed he was told, "we do not talk to athletes." While Schranz returned to a hero’s welcome in Austria, effigies of Brundage were displayed.

By the end of the 1972 Munich Olympics, there was a significant change at the head of the IOC. After 20 years -- and to the relief of many -- Brundage finally stood down as president. Many believed that his obduracy held back the Olympic movement. In his place came the Irish aristocrat Michael Morris, 3rd Baron Killanin.

In the early years of the IOC, in addition to the annual sessions, there had been regular congresses. These were gatherings with a much wider remit than the annual session. They embraced IOC members, representatives of National Olympic Committees and International Federations.

In 1973, the IOC held a congress for the first time since 1930 in the Bulgarian resort of Varna. It seemed like progress, but many criticised the fact that although athletes were at least present at the congress, none had a speaking part.

The following years were headlined by political unrest, with boycotts afflicting Montreal and Moscow. Such was the stress caused, Killanin himself suffered a heart attack and stood down after serving only an eight-year term.

He was followed by Spanish diplomat Juan Antonio Samaranch as IOC President. An official in Spain during Francisco Franco’s time, he had been posted to Moscow as Spanish ambassador. Samaranch joined the IOC two years after the 1964 Tokyo Games. Rather cruelly, one newspaper described him as "the kind of man who might emerge from an empty taxi."

In 1981, Samaranch invited a group of high profile athletes to participate at the IOC Congress in Baden-Baden, Germany. These included Bach and current World Athletics President Sebastian Coe, who both took to the stage to address the IOC membership. Coe spoke of "the support and confidence in the youth of the movement."

His speech made headlines around the world when he described doping as "the most shameful abuse of the Olympic idea."

He added: "We call for a life ban of offending athletes, we call for a life ban of coaches and the so called doctors who administer this evil."

In the wake of the Baden-Baden session, an Athlete's Commission was formed, though it was not until 1996 that representatives were chosen by the athletes themselves. That year, the Daily Olympian, the newspaper produced for athletes in the village, carried a message from IOC member Anita de Frantz, herself a rowing bronze medallist. "Starting today, every candidate will have the right to vote on a slate of 35 candidates," De Frantz said. "Each voting athlete can select up to seven people from that slate. It is fitting that at the Centennial Olympic Games the athletes will have their first opportunity to vote."

Her message said athletes "will have an important role in defining and resolving issues important to them" and will be "important, not only on the field of play but in the administration of sport as well."

In 1999, as part of the reforms which followed the Salt Lake City scandal, membership of the athlete commission carried with it a term as an IOC member for the first time. The two most recent IOC Presidents have also been Olympians. Jacques Rogge was a sailor at three Olympic Games, while Bach won team gold in fencing at the Montreal Games.

By this point, the IOC had female members in its ranks. The first two were equestrian administrator Flor Isava Fonseca from Venezuela and 400m runner Pirjo Haggman of Finland. Now 47 per cent of IOC members are female and Finnish ice hockey player Emma Terho has become the third successive woman to lead the IOC Athlete's Commission.

In reality, it wasn’t until the 1980s that the Olympics became effectively open to all. Even then, the regulations differed from sport to sport. In 1984, downhill gold medallist Bill Johnson was asked what significance the medal held for him. "Millions!" was his immediate response to the camera. Had he been around in Brundage’s time, he might well have been frogmarched from the village there and then.

The "Dream Team" basketballers, millionaires all, made their appearance at the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona. In men’s football, there had been an uneasy agreement with FIFA to accommodate the professionals where only amateurs had previously been permitted. The regulations for the men’s tournament restricted the event to under-23 players, but in the years which followed, Pep Guardiola, Jurgen Klinsman, Lionel Messi and Neymar all became Olympians.

The Olympics, then, has changed immeasurably. From politics, gender, equality, the influx of the professional and the universality of success, the Games have evolved endlessly. From Tokyo to Tokyo, this was a very Olympics to the one 57 years ago.

Source: https://www.insidethegames.biz