Birmingham 2022 is investigating launching a vaccine diplomacy programme before the Commonwealth Games to try to ensure as many athletes as possible are protected against COVID-19.

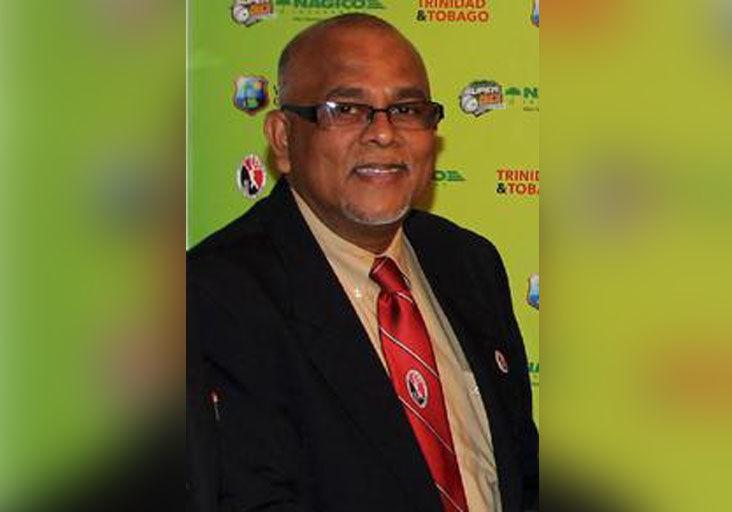

The proposal was revealed by Birmingham 2022 chief executive Ian Reid during today’s Commonwealth Games Federation (CGF) General Assembly, which was held online.

"We have been talking to the Government and Commonwealth Games Associations about rolling out a programme so that athletes who want to be vaccinated before the Games can be," he said.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) struck a deal with Pfizer, one of the main COVID-19 vaccination developers, prior to the to re-arranged Olympic Games in Tokyo.

That offered vaccines to teams before they travelled to Japan.

A similar scheme is set to be put in place before next year’s Winter Olympic Games in Beijing.

The Chinese Olympic Committee also offered to vaccinate teams before Tokyo 2020, with the IOC paying for the cost of each dose.

"We have learnt a lot from Tokyo but also what has happened in the UK (United Kingdom) where there has been a significant event research programme," Reid said.

"We think we are in a strong place but there is still nine months to go so I am sure we will continue to learn, and technology will continue to advance.

"In the UK we already have full stadia."

More than 49 million people in the UK have received at least one dose of a coronavirus vaccine - part of the biggest inoculation programme the country has ever launched.

But it is unlikely that Birmingham 2022 organisers will make it compulsory for athletes to be vaccinated before they are allowed to compete.

Reid also revealed that Birmingham 2022 is in discussions with the UK Government to make it as easy as possible for athletes and officials to enter the country.

"There is a real desire to get clarity over what everything will look like, including things like quarantine," Reid told the General Assembly.

"There’s a huge appetite within the UK Government to help, recognising the busy summer sport calendar."

CGF President Dame Louise Martin claimed that the success of Tokyo 2020 gave her optimism that Birmingham 2022 was on the right track to stage the biggest multi-sport games since the start of the global COVID-19 pandemic in March last year.

"I must reflect on a year that, despite its challenges, has given us renewed hope and optimism for the future," Dame Louise said.

"Most of you will have been involved in some capacity with the rescheduled Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games.

"There were many questions around whether Tokyo would or could take place, and so many who thought that the event would ultimately be cancelled.

"However, we all know now that Tokyo did take place, and what a spectacular sporting event it was.

"I would like to congratulate all of you, as well as your athletes, coaches, and staff, who were involved with the Games.

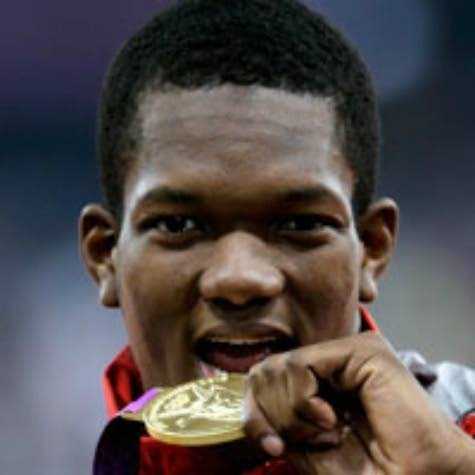

"There were so many amazing performances, particularly from our own Commonwealth athletes, that reminded us of the unique and inspirational power of a major multisport competition.

"It provides me, and I hope you, with excitement and optimism that international sporting events can soon return to their former glory, and that Birmingham 2022 is perfectly placed to take centre stage nine months from now."