So the London 2012 Olympics have come and gone in a blink of an eye and the whole of the UK still seems in a state of mourning following the euphoria and huge patriotism create by the event.

So the London 2012 Olympics have come and gone in a blink of an eye and the whole of the UK still seems in a state of mourning following the euphoria and huge patriotism create by the event.

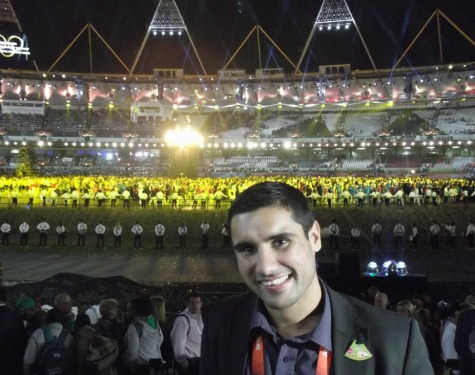

I was one of the lucky ones as I got to attend, amongst other events, both Ceremonies, the 100 metre final, the majority of Michael Phelps' victories at the Aquatics Centre and of course that legendary super-Saturday where heptathlete Jess Ennis, long-jumper Greg Rutherford and distance-runner Mo Farah all claimed golds in the space of 46 minutes.

That hour, the finest in the history of British athletics, is one I will never forget because rarely have I been in a stadium where you feel like you can touch the electricity such was the deafening atmosphere in the place.

But I have to admit, my favourite part of the Olympics was not the sport, it was actually walking around the Olympic Park and seeing thousands of spectators, adults and children alike, trotting around with a smile on their face and saying how great the Olympics was.

It was the same on London's famously rude tube where; instead of avoiding eye contact as per usual; people were talking about the Games and discussing their favourite moments. It was truly a special feeling and undoubtedly sad when that Olympic Flame extinguished in the Stadium to draw things to a formal halt.

What next?

That was the main question that seemed to be emanating from the thousands of deflated spectators that shuffled off the Olympic Park following the Olympic Closing Ceremony.

Bizarrely forgotten was the fact that London 2012 is not over because there is a whole Paralympics to come. I must declare an interest in the Paralympics because as the Paralympics Correspondent of insidethegames, I have covered almost every single element of the Games and the key players involved since we launched our dedicated Paralympic website - insideworldparasport.biz - on December 3, 2009 - exactly 1,000 days before the start of the London 2012 Paralympic Opening Ceremony.

I must declare an interest in the Paralympics because as the Paralympics Correspondent of insidethegames, I have covered almost every single element of the Games and the key players involved since we launched our dedicated Paralympic website - insideworldparasport.biz - on December 3, 2009 - exactly 1,000 days before the start of the London 2012 Paralympic Opening Ceremony.

But I am happy to admit that at the start, I did not have an in-depth knowledge of Paralympic sport.

I knew the basics: That there was a South African guy called Oscar Pistorius who controversially competes against able-bodied athletes, that Britain was pretty good at the Paralympics having finished second on the medal at the last three Summer Paralympics and that London 2012 was aiming to change perceptions of disabled people.

It was around this point that I first encountered the legendary Baroness Tanni Grey Thompson, Britain's 11-time Paralympic wheelchair racing champion, and I remember well when she told me that she "didn't care if people came to the Paralympics just because they couldn't get Olympic tickets."

"I just want them to come and then they will see what it is all about," she said.

At that point, she knew something I didn't.

Several months later, in May 2010, I headed to the BT Paralympic World Cup in Manchester and on the eve of the event, I met Pistorius himself.

In a long one-on-one interview with the South African, I remember grilling him about why he still wanted to compete at the Paralympics if he could make the Olympics, which he ultimately did. His message was remarkable similar to the one Tanni gave me.

His message was remarkable similar to the one Tanni gave me.

"It's not a second grade version of any able-bodied sport," he told me.

"It's got triumph; it's got disaster and it's got everything else you need for great sport."

I didn't fully understand what he was talking about either until a day or so later when I settled down to watch my first wheelchair basketball match – Britain v Australia.

Within seconds of the first brutal collision of wheelchairs, I realised what I had been missing. It was a game with as much skill, precision, ability and power as any sport I had seen before. I was completely hypnotised by the fact that these athletes that we would could "disabled" appeared be more able than most.

Several years on, we reach the London 2012 Paralympics, and like Tanni and Oscar, who I am now lucky enough to call friends, I know what is coming. I will be one of the few at the venues that will not be surprised at how phenomenal the athletes are.

I was reminded of it just this week when I went to see the Japanese Paralympic swimming team train at Basildon Sporting Village, not far from where I live.

The pool has a glass window so that the public can see in and a mother and her two young children were walking past as one of the Japanese swimmers with no arms performed a superb dive into the pool.

As he dived, I saw the mother and her children stop suddenly in their tracks, with their mouths open, at the remarkable achievement.

They then pressed their faces to the glass for a closer look and stood there for several minutes. As I turned back to the pool, all I saw was the swimmer wearing a frown because the dive had not been performed absolutely perfectly.

As I turned back to the pool, all I saw was the swimmer wearing a frown because the dive had not been performed absolutely perfectly.

I imagine I will see a lot of shocked and surprised faces in the crowd at the Paralympics.

I myself had one when I first saw Paralympic sport and realised what these athletes can do.

But once that surprise wears off, and it will do quickly, I know that Britain will sit back and enjoy world class sport just as they did at the Olympics.

Why?

Because they will quickly realise the Paralympics is not a second grade version of any able-bodied sport.

Source: www.insidethegames.biz